Holding Space: Summing Up the PDC Occupation

Note: We are excited to publish the following document which was submitted to Mass Struggle by a group of activists who were involved in the People's Democracy Center occupation during Summer 2024, some of whom are supporters of our organization. We are sharing this summation because we believe the analysis drawn out here provides an important perspective on this struggle and contains crucial lessons for future efforts.

The authors of this document can be contacted at occupation-summation-committee [at] proton [dot] me.

INTRODUCTION

On April 5, 2024, resident organizations of the Democracy Center (DC)—a non-profit community center and organizing hub in Cambridge, Massachusetts—received notice that the space was scheduled to close, and that they would be evicted on or before July 1 of that year. As we will develop below, this closure was motivated by a two-headed monster: on one hand, contradictions between anti-Zionist groups and the Foundation for Civic Leadership (FCL, the parent organization of the DC, who refused to deny service to Zionist organizations who had been using the space), and on the other hand, a broader tendency of gentrification in the Harvard Square neighborhood which was sharpened by post-COVID economic conditions.

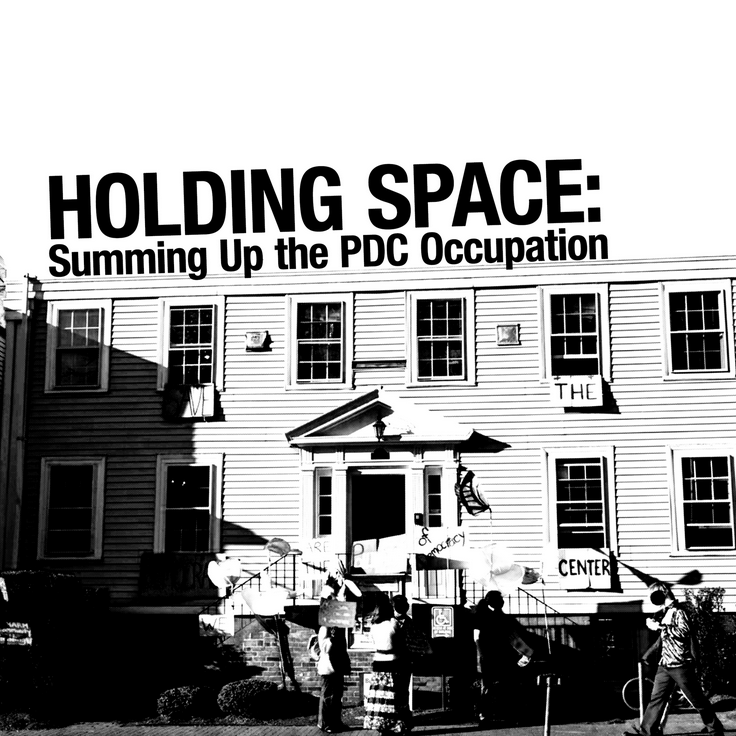

In response to the closure announcement, and after a period of aboveground negotiations (the ‘Save the DC’ campaign) which were unable to forestall the eviction, activists occupied the DC beginning late in the night of June 30, ultimately declaring the reclaimed building to be the “People’s Democracy Center” (PDC).

We are a group of communists who individually participated in the PDC in various roles, and who came together after uniting around shared criticisms of the course of the occupation. In the days following the evacuation, we leveled an uncomradely and overly polemical criticism towards others debriefing the struggle. We are publishing this document in the interest of rectifying the mistakes we made in that early phase of criticism/self-criticism, and in order to more substantively identify some of the political and practical errors made throughout the PDC struggle. By analyzing these events we aim to draw out our understanding of the key fault-lines which led to the collapse of the struggle, as well as the reasons for the political isolation of the occupiers from the broader movement “outside” the building, to inform our approach in future political work.

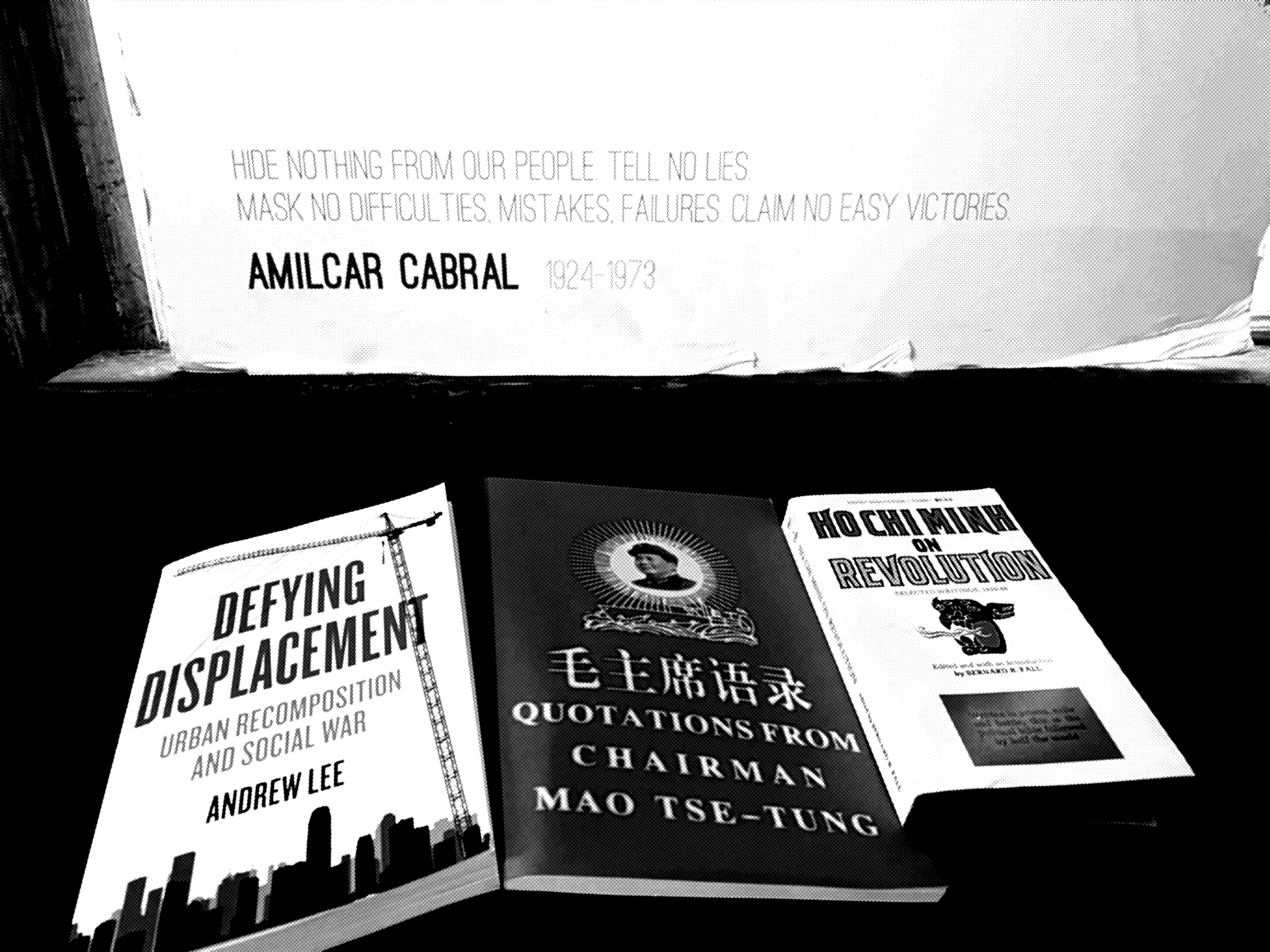

By openly proclaiming our communist politics, we aim to be honest about our partisan, working class perspective. We do not claim to approach our analysis from an ostensibly neutral or unbiased orientation, but instead to bring a clear political viewpoint which can enable us to sum up and evaluate the PDC struggle systematically, from the point of view of the broader revolutionary movement.

As communists, we understand the relationship between political theory and social practice to be a dialectical one. By this we mean that broader theoretical principles must be drawn out through analysis of revolutionary practice, and in turn each sequence of political struggle must be guided by theory. By summing up sequences of political work, identifying what advanced the sequence and what held it back, learning from our mistakes and compiling the new ideas produced by the creative forces of class struggle, we enable the movement to learn and grow.

In order to do so, we must seriously evaluate the successes and errors which occurred within this sequence of work, and attempt to draw out their root causes. This means that we must be open in our criticism of errors. While we recognize that the content of a criticism holds more importance for the task at hand than the form in which it is presented, we hope to make clear that this is not an attack on those who advanced lines which we identify as having been detrimental to the course of the sequence (which includes ourselves), but rather an evaluation of why these lines were incorrect and how they came to shape the course of the struggle. It is only through open criticism and self criticism that we can truly draw out lessons and forge a path forwards.

The development of any sequence of political activity is driven by the dominance of a general line which informs how the situation is understood, and how decisions about the struggle are made. This is never a static situation; in all sequences and in all organizations, there is a constant struggle between these lines which reflects the influence of the class struggle on the ideas of the individuals involved. Furthermore, at different points in a sequence this struggle between lines may take on a more or less open, and more or less confrontational character. Below, we outline our analysis of the key line struggles which we believe determined the development of the PDC sequence.

1. Putting Politics in Command

To our view, the key question which guided the development of the PDC struggle was “were politics in command?” Throughout all periods of this sequence, there was sharp disagreement over whether, and how, the occupation should relate to existing, “outside” political struggles, particularly the anti-Zionist movement and the fight against gentrification. This debate took different forms in different periods, but the dominant line throughout the sequence was in favor of a clear de-politicization of the struggle, refusing to meaningfully link up with forces with whom we shared common enemies and suppressing efforts to inject the work with a political character or articulate its concrete relationships with other social forces. Our grouping’s failure to consistently wage the two line struggle over these questions was our key error during the events of the occupation (and preceding period), and the political vacuity resulting from this enabled ruling class ideas to take root, leading to the atmosphere of unaddressed chauvinism characterizing the final days of the sequence. This reflected a liberal culture of refraining from criticism/self-criticism which was endemic to both the SDC and PDC periods, corresponding to a desire to maintain a vague, unprincipled unity. Consequently, right-opportunist positions were often taken up by default, merely because there was neither an avenue for criticism, nor a culture of it.

2. De/Centralization

Another key question was that of leadership, and how the decision-making practices of the occupation should be structured, particularly in terms of the occupation’s relationship to the former resident organizations of the DC. Throughout the sequence, the dominant line on this question was one advocating decentralization and disorganization. This was a consequence of the dominance of a tendency which emerged during the ‘Save the DC’ campaign period (and subsequent preparatory stages of the occupation) which fiercely resisted the development of a leadership structure empowered to do anything beyond coordinating the completion of immediate practical tasks. This structure was consequently defended from criticism on the basis of ideological fidelity to certain anarchist principles dominant within the SDC campaign milieu, some of whom continued on to participate in the PDC struggle. Despite this allegedly horizontal structure, real leadership did emerge, in the form of an unaccountable, informal clique which overrode previous large-group decisions at will. In addition, this grouping advocated for making decisions only through consensus, but refused to identify who needed to be in consensus for decisions to be made, or how these decisions would be enacted.

3. Identifying and Uniting with the Real Masses

Lastly, and derived from the above, was the question of the masses: was it necessary to win over mass support for the occupation, and if so, to which “masses” should we go? As communists, we maintain that this is a decisive question: it is the masses who make history, not small groups of activists acting on their own. A struggle which refuses to unite with the masses, laying bare the connection between their immediate interests and the objectives of the movement in order to win their support, is doomed to failure. But in the case of the DC occupation, the dominance of a line outright opposed to politicizing the struggle made linking up with the masses impossible: without politics in command, we could not clearly articulate in whose interests the struggle was being waged, and therefore no meaningful efforts could be made to unite with anyone but the activist milieu who was already aware of and had relied on the DC. This de-facto emphasis on the activist milieu was primarily a consequence of mobilizing already-existing social ties, which resulted in the development of an environment which was welcoming primarily to those initially involved in the efforts to save the Democracy Center, or their immediate social connections, but alienating (when not openly hostile) to others. This method of affinity-based organizing proved to create an environment which was unwelcoming to the community and accommodating of white chauvinism on the part of key organizers whose social credibility made them informal “leaders” despite the avowedly horizontal structure of the occupation.

BACKGROUND

All social movements take place within a nexus of local and global struggles, reflecting the balance of forces accumulated by the revolutionary classes and our enemies at any given time. Failing (or refusing) to grasp which of those contradictions are primary within a given sequence prevents us from developing a political line which follows from a concrete analysis of the situation and the objective factors which determined its development. Without examining these contradictions, decisions about strategy and tactics can only be dictated by subjectivism based on the narrow, personal perspective of individual decision makers rather than an all-sided account of the situation in its complexity.

In the absence of the clear political orientation provided by a concrete analysis of the situation, even a struggle that successfully wins its basic demands (such as preventing the eviction of a community center) will never be able to link up with the broader fight against the structures which produced the situation in the first place, and will certainly never mobilize the broad masses behind its calls to action. Such was the case with the struggle for the People’s Democracy Center, which both failed to win its demands and failed to win broad support for the occupation. This was due, in no small part, to a failure to articulate the actual political stakes of the struggle to the public, and to a lack of unity in perspective regarding the concrete situation with which we were faced. It is difficult to overstate how deference to the de-radicalizing line put forward by the NGOs during the SDC period contributed to this obfuscation.

For our part, we find that fundamental to understanding the struggle for the People’s Democracy Center is the task of situating it within the broader process of capitalism, at the local level through the gentrification of Harvard Square and the role of the nonprofit industrial complex in defanging political movements, and at the international level through the relationship between u.s.a. financial capital and the imperialist plunder of Palestine. By failing to root ourselves in a shared understanding of these contradictions, particularly the struggle against Zionism, we stunted our ability to think strategically, isolated ourselves from the masses, and enabled our own encirclement and defeat. In order to more productively move forward and provide an all-sided view of the PDC struggle, we aim to clarify our analysis of these contradictions and the objective situation prior to the initiation of the occupation.

We will begin our analysis by providing a brief overview of the political economy of gentrification in Harvard Square in order to expose the structural impetus for the displacement of Democracy Center tenants, and then link this account to the role played by the “non-profit industrial complex” in the maintenance of u.s.a. capitalism (and the balance of forces within the pre-occupation ‘Save the DC’ campaign). Finally, we will discuss the relationship between the ‘Foundation for Civil Leadership’ decision to evict the DC resident organizations and the struggle for the national liberation of Palestine from u.s. imperialism and israeli occupation.

We insist that the question of Palestinian liberation is linked to u.s. imperialism because, while the israeli settler-colonial project is the immediate adversary of the Palestinian revolution, that project is propped up by, and for the benefit, of u.s. finance capital. That is, we adhere to the Leninist definition of imperialism, that it is “monopoly capitalism; parasitic, or decaying capitalism; moribund capitalism,”:

“The supplanting of free competition by monopoly is the fundamental economic feature, the quintessence of imperialism. Monopoly manifests itself in five principal forms: (1) cartels, syndicates and trusts—the concentration of production has reached a degree which gives rise to these monopolistic associations of capitalists; (2) the monopolistic position of the big banks […] (3) seizure of the sources of raw material by the trusts and the financial oligarchy (finance capital is monopoly industrial capital merged with bank capital); (4) the (economic) partition of the world by the international cartels has begun […] The export of capital, as distinct from the export of commodities under non-monopoly capitalism, is a highly characteristic phenomenon and is closely linked with the economic and territorial-political partition of the world […]”

Lenin’s emphasis on imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism is key: the development finance capitalism (monopoly industrial capital merged with bank capital in the form of the multinational corporation which controls production via interlocking chains of holding companies and stock ownership) drives the imperialist repartition of the world chiefly in order to secure markets for the export of capital. Capital exports (generally in the form of ‘foreign direct investment’ or FDI) enable the bourgeoisie of the imperialist countries to reinvest overaccumulated capital (capital which can no longer be productively invested at home, because of the same tendency towards falling profitability which drives the process of concentration and monopolization) in regions where a profit can still be made because of lower wage levels and production costs. The finance capitalists then reap the benefits of the surplus value generated from production in the countries dominated by imperialism through the forcible extraction of returns on their investments.

Despite its role as a junior partner in the imperialist project and its relatively advanced industrial economy, israel is still a major market for capital exports of this type, receiving millions in FDI each year towards its lucrative R&D and manufacturing sectors (in addition to the aid packages supporting its military program).[1] This began in 1985 with the passage of the ‘Economic Stabilization Act’ by the israeli government, which opened the market to traditional FDI.[2]

Relatively stable profitability trends in the israeli economy (despite the industrial concentration in sectors with often astronomically high levels of technical composition, which trend towards declining rates of profit at the international level) are bolstered by the use of the Palestinian proletariat as a captive, migrant workforce. Fluctuations in the employment levels of Palestinian workers in the israeli settler economy correspond to periods of high and low productivity overall, and are artificially maintained by conscious planning on the part of the israeli capitalists (who alternate between employing Palestinians and imported labor from Asia and Africa). Furthermore,

“The Palestinian economy is completely integrated into and dependent upon the israeli economy. Approximately 75 percent of all imports to the WB/GS originate in israel while 95 percent of all WB/GS exports are destined for israel. israel’s complete control over all external borders mean that it is impossible for the Palestinian economy to develop meaningful trade relations with a third country. The WB/GS are highly dependent on imported goods, with total imports amounting to approximately 80 percent of GDP. In such a situation of very weak local production and high dependence on imports, the economic power of the Palestinian capitalist class does not stem from local industry or production, but is comprador in nature. Its profits are drawn from the exclusive import rights on israeli goods, and control over large monopolies that were granted to those loyal to Arafat. The privileged relationship with israeli capital is the defining feature of the Palestinian bourgeoisie.”[3]

This structure—a permanent reserve army of workers and a captive market for israeli commodity exports for the benefit of investments made by multinational finance capitalist firms—is coupled with the use of israel as an outpost to defend the regional interests of u.s. finance capital, ensuring access to natural resources (chiefly oil) and other capital export markets in the Middle East.

But the relentless pursuit of new outlets for productive capital by the finance capitalists is not limited to the oppressed countries; they are actively in search of any opportunity for productive investment, and the cycle of gentrification is intimately linked to this process.

Gentrification and Rent in Harvard Square

Understanding gentrification requires grasping how rent extraction is accomplished by the landowning capitalist class: extracting value from the broader economy, mediated through the monopolization and commodification of land. Unlike capitalist accumulation occurring through ownership of the means of production, rent is necessarily not directly generated by productive labor on the land but appropriates part of the surplus value created in other sectors of the economy.

Gentrification intensifies rent extraction by replacing lower-value uses (e.g., affordable housing, small businesses) with higher-value ones (luxury developments, high-end retail, etc.). Redevelopment projects amplify land's exchange value, ensuring landlords capture a growing share of surplus value from tenants who themselves profit from urban labor and commerce.

This is further mediated by finance capitalist investment: land increasingly serves as a speculative asset in urban centers, with financial institutions investing in property markets to secure returns. This drives up land values and rents, further commodifying urban space and heightening the extraction of surplus value through rent.

In Harvard Square, rent differentials are the product of proximity to the university, which serves as both a tourist attraction and a center of productive capital, employing thousands of workers from administrators and academic professionals to maintenance staff and groundskeepers. This allows landlords to extract higher rents than other locations in Cambridge, even when the actual costs of maintaining the property are comparable.

Notably, the question of property maintenance is directly tied to the gentrification cycle. Rent extraction requires the generation of surplus value elsewhere in the economic value chain, part of which is then appropriated by the landowning capitalist. The amount of rent extracted, the real estate rent of a particular parcel (understood as the difference between its current market price and its price at the time that the building was constructed), is structurally determined in circulation. The following argument, which we quote at length, develops this analysis in the particular case of housing, but applies just the same in the case of commercial real estate rents:

“Real estate rent is the determination of stock prices by current prices. It depends on a long-run increase in the market price of housing. This can be produced in one of two different ways:

(1) The building is maintained in the normal housing market thanks to regular investments that maintain (or even improve) the building, which allow prices to be fixed at the regulating price of new housing – the magnitude around which market prices oscillate.

The regulating price of new housing is in part determined by a sectoral surplus profit (which can be fixed as an absolute rent) whose practical source is the high organic composition of capital in the construction industry, marked by relatively-backwards technical relations of production and stagnant productive forces. This factor leads to a persistent rise in relative prices in the normal housing market.

(2) The housing is abandoned to progressive degradation, via a policy of disinvestment. The price falls relative to new prices, and the housing enters the sub-normal housing market. However, while disinvestment leads to an immediate fall in prices as housing changes markets, the internal price dynamics of the sub-normal housing market are characterized by long-run price increases.

There is no regulating price in the sub-normal housing market, because below-average profitability there means that supply cannot be fed by new capitalist production, but rather mainly grows through the deterioration of existing housing stock. Where new sub-normal housing is fed by capitalist production, such production is subsidized by the state [e.g., by HUD]. A systematic gap is thus formed between the market price of housing and the current conditions of production or maintenance, so that prices are uniquely determined in the sphere of circulation. The result of this structural weakness of supply is a monopoly price of shortage that leads to long-run real increases in housing prices.”[4]

Renovations or redevelopments—such as converting older properties into luxury apartments, boutique retail spaces, or upscale offices—augment the capacity to command higher rents in the immediate sense, while also increasing the shortage of subnormal housing, driving up real estate rents overall. These investments thus double as a means to capture surplus value produced in other sectors while also enabling landowning capitalists to speculate on the possibility of future rents in the subnormal sector and tendential increases in property valuation in general.

The result is a cycling landscape of deteriorating buildings (both housing and commercial plots) reserved for the lowest sectors of the working class and upscale amenities for the scions of the ruling class, escalating property values and rents in both markets through a vicious process of abandonment and reinvestment.

Harvard University is itself a key landowner, controlling large swaths of property either directly or through subsidiaries, including 10% of available real estate in Cambridge and 6% in Allston, including massive swaths of subnormal housing in the “Lower Allston” neighborhood. This portfolio is managed by Harvard Real Estate, which controls land assets worth approximately $10B around the world.[5] They are a key participant in the cycle in question. However, while driven by large institutional landlords such as Harvard, the gentrification process is certainly not specific to the university: it is inconsequential whether Harvard directly owns a particular plot, insofar as the overall tendency towards greater rent extraction is not the product of an individually greedy landlord but the overall system of capitalism itself.

This process of deliberate neglect and disinvestment by the owners of subnormal commercial spaces was directly tied up in the logic of the Democracy Center closure by its owners (the ‘Foundation for Civic Leadership’). FCL, via its lackeys, justified the decision to evict according to the need for “renovations” of the space.

FCL and the Nonprofit Industrial Complex

Sue Heilman, the interim executive director of the FCL program behind the Democracy Center, described this decision in terms that echo the language of ‘urban renewal’ in an email to the Harvard Crimson:

“The driving factor behind this decision is the need for substantial repairs and refurbishments to the building...Conversations about its physical condition have been occurring for a long time, and after being well-used by the community for 22 years, repairs are long overdue.”[6]

Of course, there is no evidence that these allegedly imminent renovations (which were also used as a specter to justify the police eviction of the Occupation in July) have actually been planned:

"[FCL] doesn’t have permits, plans, a builder, a timeline for the work or money budgeted, said Sue Heilman, the interim executive director of Democracy House, during April meetings with angry and worried tenants.

Peter McLaughlin, commissioner of the Cambridge Inspectional Services Department, confirmed that there are no permits on file for the address of The Democracy Center, and finding someone to do the hands-on work is the bigger problem: “Usually, good contractors are booked for a year or two in advance,” McLaughlin said.

Asked why the foundation was expelling organizations if a long permitting process had not begun, Heilman wrote: “FCL is in the process of investigating what the renovations could include and expects to be filing for a building permit as soon as the plans are completed.”[7]

Instead, the eviction procedure has merely displaced resident organizations – many of whom operated out of the Democracy Center for years – in order to “refurbish” the space, making it more attractive to the influx of finance capitalist investment in the Harvard Square area.

While FCL maintains its promise that organizations will be welcome to return once the allegedly necessary renovations are complete, it should be obvious to any observer that the type of organizations which would be welcome in a “revitalized” Democracy Center will not reflect the vibrant diversity of its pre-eviction community. This is evidenced by the very real pattern of displacement changing the face of non-profit organizations in the Harvard Square and Cambridge area from the 1970s to today:

“Cambridge was once home to a third of all organizing spaces in Greater Boston...The physical visibility of storefront organizing spaces depended upon the cheap rent that existed in Cambridge at that time – cheap rent which was made possible by prior racist redlining and organized abandonment that had devalued real estate in Cambridge’s historically Black and immigrant neighborhoods. As universities expanded into these neighborhoods and displaced their residents, rents increased and many radical groups couldn’t afford to stay.

[…] The landlords of Sanctuary (74 Mt. Auburn St), a shelter and provider of counseling services for people experiencing homelessness, sold the building to Harvard in 1974, who terminated the lease; today it houses the Harvard Office for the Arts. A feminist cooperative daycare (46 Oxford St) survived a move into a Harvard-owned building only to become a $2,780/month daycare serving Harvard parents. Other Ways, an alternative school at 5 Story St, was swallowed up by Harvard’s campus. Organizations not directly replaced by universities were destroyed by their effects on the real estate market. In 2015, a triple-decker at 186 Hampshire St that lefty landowners had been renting affordably to radical groups for 40 years was seized by the city for back taxes (for most other landlords, rising property values are enough to kill low rent).”[8]

Notably, the closure of the Democracy Center—unlike many of the above-mentioned closures—was driven by an organization which serves as both operator and landowner of the community space in question. This represents an unusual situation, given that the typical process of non-profit eviction follows from an increase in rent expectations by a third-party landlord; in this case, the unilateral decision by FCL to close their own space was not driven by a desire for rent maximization, but instead by pressures to “revitalize” the space in accordance with the overall process of gentrification in Harvard, and contradictions between FCL and the social movements which called the DC home.

To better understand why this contradiction sharpened to the point of eviction, we must first lay out what precisely FCL is, and who composes its leadership.

The FCL describes itself as “a nonprofit dedicated to engaging the next generation of democracy” which works with partners to “identify gaps in the field, incubate new scalable projects to help fill them, and support those projects in becoming independent and sustainable.” Its founder and president, Ian Simmons is a “progressive investor” who graduated from Harvard Business School, training ground for the profiteering vultures of the venture capitalist world, in 2000.

Simmons is also the principle financier behind Blue Haven Initiative, which “deploys diverse forms of capital to address social and environmental challenges, while also maintaining an unwavering commitment to investment excellence and cultivating leadership to effect transformative change.” This takes the form of large scale investment in fixed-rate mutual funds, public and private equities, debt-financing credit firms, and direct investment in the countries oppressed by imperialism, primarily in the financial services and health sectors. These direct investments, despite being framed as “developmentalist” and “progressive,” are explicitly conducted with the objective of securing market rates of return:

“As one of the first family offices created with impact investing as its primary mission and focus, Blue Haven seeks market rates of financial return on its investments as well as maximum social and environmental impact. We take a total portfolio approach to managing investments across asset classes, applying rigorous portfolio-management principles as part of our investment strategy.”[9]

The imperialist strategy of investment in “non-governmental organizations” to manage the exploitation of the oppressed nations is hardly new, and the “progressive” veneer afforded to investors such as Simmons is a core part of this strategy. We quote at length from a document produced by comrades in India responding to the NGOs of the ‘World Social Forum’ of the early 2000s:

“Ever since the onset of the present phase of globalisation and liberalisation in the late 1970s, and particularly since the collapse of the bureaucratic capitalist states in the Soviet Union and East Europe in the late 1980s, a new propaganda campaign with fashionable, radical terminology is being unleashed by international capital in the subtlest of ways. The vehicles of the new vocabulary are the so-called Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) that have proliferated on a massive scale.

The new vocabulary of the NGOs is ‘empowerment’ of the deprived sections, ‘civil society’, ‘anti-statism’, ‘social justice’, ‘human rights’, ‘identity movements’, ‘sectional movements’, ‘self-help’, ‘community development’, ‘sustainable development’, ‘participatory democracy’, ‘environmental protection’, and so on. It is not surprising to see the same vocabulary in the documents of the World Bank, ADB, and other UN agencies and UN-sponsored World Summits. It may look paradoxical that the very same imperialist agencies that vigorously promote liberalisation and globalisation all over the world are also the ones promoting the concepts of grassroots democracy, empowerment, human rights, and so on.

But if one analyses the strategy of the exploiting classes we find that it is the most common thing to resort to both repression and reform simultaneously. While letting loose the worst type of massacres on the struggling masses, the same fascist governments also dole out funds for so-called welfare schemes, development activity, and so on, at least for a tiny section of the population. Worse still, they even talk at times of human rights violations by their own mercenary forces and set up human rights commissions.

[…] Huge funds are thus poured into the coffers of the NGOs in the name of development, social justice, human rights, grassroots democracy, etc. In the past decade the World Bank and other UN agencies have been insisting that funds should be utilised through the NGOs. So do the various governments. With such huge funds at their disposal the NGOs act as elitist organisations completely divorced from the masses. Yet they focus themselves as benefactors for the people. It is estimated that hardly 10-15% of the allocated imperialist funds reach the needy people while most of it goes for the maintenance of the NGO establishments and the running expenditures of the so-called volunteer workers.”[10]

The employment of this strategy is hardly unique to the imperialist domination of oppressed nations: the co-opting or institutionalization of dissent is just as common for the management of social struggles within the imperialist countries themselves.

NGOs, including nonprofit organizations, particularly those operated for the “benefit” of oppressed national minorities within the u.s.a. prisonhouse of nations, function analogously to the strategy of neo-colonialism: the management of the super-exploitation of oppressed peoples by “representatives” of those peoples themselves, offering basic social services (“doing good work”) while siphoning energy away from organized resistance and into careers within structures that pose no challenge to capitalist rule.

Such organizations crop up in huge numbers in the wake of instances of mass rebellions like the George Floyd Uprising or the more recent wave of student struggles against Zionism, functioning as a safety valve through which the momentum of social movements can be integrated into the day-to-day functioning of the system. Rebel activists born in the crucible of class struggles are recruited into roles within legal organizations with 501c3 status, and then their obligation to operate within the paradigm of ruling class legality (in order to retain access to funding or prevent loss of nonprofit status) blunts their ability to confront the real abuses of the system.

We again quote from the Indian comrades:

“[The strategy of the NGOs pushes] a non-class struggle-based approach and thereby covers up the reality of class contradictions in society. They are vehemently anti-communist, and while criticizing the present system, they have no alternative, except fairy-like utopias. They are fanatically against violence and ask the people to face the monsters that run this system through dialogue and communication, expecting a change of heart. They are isolationists, with each group only interested in the impact of globalisation on their particular field - be it women, dalits, tribals, the environment, etc. The ‘debate’ that takes place at such forums is rarely ideological - mostly confined to puerile repetitions of post-modernist formulations in the abstract…They tend to be highly empiricist, glorifying their so-called grass-rootism and micro experiences, and building theories around their limited worlds. It is like building castles in the air. In this schema there cannot be any fruitful ideological ‘debate’, but the mere pitting of one experience against another. This negation of ideology, and particularly Marxist ideology, is the most effective tool of these NGOs to prevent their ranks from going into the problems of society in depth and drawing conclusions from such analysis. So they have only a superficial view of imperialism, noticing some of its ill effects, which they feel can be reformed. They seek therefore to remove the symptom, rather than cure the disease.”[11]

Who among us can claim not to have encountered such an orientation from non-profit scene activists? The legalism and narrow political scope of such organizations is of particular note here, given the predominance of these “progressive” NGOs among the resident organizations threatened with eviction by the DC closure. As the course of the struggle for the DC sharpened in the lead up to the occupation, the role of these groups was to push for an accomodationist line rather than to organize resistance to the eviction. This was justified by citing to the need to ensure their 501c3 status (and therefore the salaries of their paid staff) was not threatened by association with any escalations deemed to be “illegal.” While this influence mainly impacted the course of development of the Democracy Center struggle during its ‘Save the DC’ campaign period, such opportunism is common throughout the mass movement.

We developed the above analysis in order to demonstrate how individuals like Simmons serve as a key link between the strategy of imperialist rule in the oppressed nations and this strategy of dissent management at home. The portfolio of investments BHI represents spans from the operation of the Democracy Center and the “incubation of scalable (profitable) projects” for engagement with democracy in the u.s.a., to the funding of developmentalist NGOs in central Africa that prop up neo-colonial governments.

For over two decades, under Simmons’ loose management, the Democracy Center served as a space where such non-profits could operate and develop. It also served as a space where any number of legitimately progressive organizations, cultural groups, art collectives, and individuals could meet, collaborate, and organize. For much of its life-span—thanks in no small part to a particular DC employee’s tireless efforts to facilitate that monumental undertaking—the contradiction between these two tendencies was more or less manageable.

All that changed in the wake of the heroic Al Aqsa Flood of October 7 2023, when brave fighters of the Palestinian resistance struck a massive blow against the Zionist occupation of their homeland. Suddenly, and for the first time in decades within the u.s.a., the question of israeli imperialism became a firm dividing line between genuinely progressive forces and the reformists and opportunists who would rather sell-out the Palestinian people to genocide than risk their privileged status.

Here, the link between Simmons, Blue Haven, and FCL becomes critical, as the list of third-party private equity investments managed by Blue Haven Initiative includes a sweeping number of international finance capitalist firms, from Goldman Sachs to Bain Capital, who directly invest in israeli weapons firms.

When, in the fall of 2023, it was exposed that Zionist organizations (including one which brought IOF officers to speak at its events) were allowed use of the DC, a struggle broke out and a campaign was mounted to force the DC leadership to ban such organizations from its space. It was their refusal to do so—motivated in no small part by Simmons’ economic ties to israel, as well as the personal offense he took at being challenged for his actions—which transformed this contradiction between the non-profit orientation of FCL and the progressive forces (which relied on the key resource the DC offered) into an open struggle, culminating in the April 2024 decision to shutter the space.

It should thus be immediately apparent that the stakes of the struggle to save the Democracy Center were linked intimately to both resistance to gentrification and to the struggle against Zionism, two concrete mass movements with whom the occupation could have been in solidarity. Linking up with these movements by demonstrating to the masses how the occupation of the DC was tied to their concerns should have been a matter of basic principle, not to mention tactical pragmatism.

Instead, reticence to “appropriate the language of displacement,” particularly from the nonprofit elements within the ‘Save the DC’ campaign, resulted in the occupation’s ambiguous sense of its own politics and its objective isolation from the broader mass movement, unable to mobilize mass support because it was unsure of what it could call support for. Rather than attempt to understand itself in relation to other struggles, it reduced itself to aiming to save a community center—a noble but insufficient goal.

Below, we will outline the course of events beginning from the eviction announcement in April through the struggle itself.

THE ‘SAVE THE DC’ CAMPAIGN AND THE DIRECT ACTION WORKING GROUP

On April 5, 2024 recipients of the Democracy Center's newsletter received an email informing them of the planned closure on July 1. The announcement read,

"The DC’s fiscal sponsor, the Foundation for Civic Leadership, has made the difficult decision to close the Democracy Center effective July 1, 2024. The closure will be used to make necessary renovations to the building, with the hope that in the future we will be able to welcome community groups once again. Operations will run normally until the Democracy Center’s closure, including all scheduled events prior to July 1, 2024."[12]

The closure notice included a link to sign up for two subsequent community meetings to discuss the plan for closure and links directing people to other community spaces in the area.

These community meetings were lively and emotional affairs, during which multiple resident organizations entered into direct confrontation with the FCL's representatives and exposed their covert agenda of gentrification. Immediately FCL’s vague claim to "hope to welcome community groups in the future" and their inability to specify which renovations necessitated closing the space were identified as evidence of their duplicity. FCL's history of tolerating openly Zionist organizations was passionately challenged at one of the meetings.

These positions were met with predictably ghoulish indifference on the part of FCL's leaders and were further stifled by the methods of organizing dominant in the immediate reaction to the closure notice under the influence of the NGO resident organizations.

During the community meetings, speaking time was allocated according to the economic relationships between the various groups and the DC. Those groups with rental agreements to secure permanent offices in the space—namely, the liberal NGOs—were given the most immediate priority while those organizations who used the space for free (which we will refer to here as ‘community organizations’) were given the lowest priority. This choice in agenda-setting set an opportunist precedent which became dominant throughout the development of the struggle, whereby long-term political questions were sacrificed in favor of winning short-term gains for the most influential or well-funded elements. As we will see, however, this orientation failed to even secure those gains.

In the wake of the struggle emerging from the community meetings, activists from a variety of groups—both resident nonprofits and community organizations—organized themselves into four working groups: Pressure, Logistics, Public Relations, and Direct Action. The public face of these working groups was referred to as the ‘Save the Democracy Center’ campaign, (SDC). An Advisory Council composed of representatives from each working group was also established, setting a precedent whereby political decision-making and democratic practice was sidelined in favor of structures which merely coordinated practical activity. These working groups collaborated effectively in the early stage of the struggle, but as the date of the closure approached, differences in analysis between the Direct Action working group and the legal, non-profit orientation of other sections of the campaign began to sharpen, revealing the clear divisions within the coalition.

That is, while the Direct Action working group advocated for a united front of direct opposition to an act of gentrification and conciliation with Zionism, the right-opportunist NGO line fought to ensure that the campaign instead became a disorganized bloc of interest groups with purely economic demands to stop the closure or rehouse their organizations elsewhere. The left line within the Direct Action working group consistently failed to take the initiative in waging the struggle against the right-opportunist line, due primarily to a liberal reticence to ‘pick fights’ often resulting from the influence of the internal right line within the working group, which, while anti-Zionist, aimed to conciliate with the other SDC forces rather than force a break.

This difference in orientation was informed in no small part by the distinct composition of the working groups: unlike the right-opportunist elements concentrated in the Advisory Council, the Direct Action working group was composed primarily of members of community organizations, many of whom had previously been involved in the campaign to oust the Zionist organizations from the DC. Consequently, members of that working group had a more consolidated political outlook than other sections of the SDC campaign. While other working groups would make appeals to authority figures in the web of Ian Simmons' professional nonprofit connections to intervene, the Direct Action working group emphasized the necessity for disrupting the eviction process directly and consistently rejected tactics which relied on expecting FCL to operate in good faith. A plan of escalation was drafted, up to and including illegal occupation of the space, which further sharpened internal conflict between the Direct Action working group and the right-opportunist elements within the campaign, despite the fact that the escalation plan was never actually imposed.

One example of this internal struggle was related to a Palestine solidarity banner which was hung from the DC windows in the weeks leading up to the occupation. Previous discussion within the Advisory Council had indicated a general consensus among the working groups that banners needed to be made, and the working groups were entrusted to make them according to their own decision-making processes. Consequently, members of the Direct Action working group—who had previously collaborated on the anti-Zionist campaign within the DC—made a banner which read: "Resist Displacement from Gaza to Cambridge! Save the DC!" depicting the Palestinian flag. This prompted considerable backlash in the form of liberal moralizing regarding “appropriation” of anti-displacement and anti-Zionist language, reflecting a resistance on the part of the right-wing of the campaign to any reference to other political struggles, an attitude which remained prevalent even during the occupation itself. Liberal hand-wringing aside, such an orientation belies the low political level of a coalition unable to recognize the central position of both the NGO-industrial complex and institutions such as Harvard University (the main force behind gentrification in Cambridge) in propping up the Zionist occupation of Palestine.

In the contentious meeting which followed, the Direct Action working group were ultimately able to force the opposition to admit that failing to make this political connection at all would be a far greater error than making the connection in an apparently “vulgar” way. This also exposed the degree to which their contestation amounted to concerns about word choice and language, and the degree to which the right-opportunist line considered public image to be more tactically important than unity around basic anti-Zionist politics. But this rift between the most advanced elements of the Direct Action working group and the rest of the SDC could not be bridged by this debate, and the decentralized nature of the SDC organizing would only solidify the Direct Action working group's increasing isolation from the other elements of the campaign. This decentralization was particularly expressed by the Advisory Council’s refusal to act as leadership, insisting instead upon acting merely as a coordinating body.

The Advisory Council was of mixed composition, including representation from both resident NGOs and community organizations; consequently, when the groups with rental agreements moved out of the space and found new places to set up, the AC was unable to consistently lead the struggle. The predictable de-mobilization of the campaign after leadership elements effectively capitulated to FCL is a key example of the limits of the strategy adopted by the SDC (of “negotiating” without leverage).

Following this demobilization, the SDC campaign degenerated into attempts at “negotiating” with FCL regarding the future of the space. This endeavor was doomed from the outset: negotiations such as this require the expectation that each party is engaged on essentially equal terms, which is certainly not the case in the context of a “legal” eviction process, during which the SDC campaign organizers lacked any leverage against FCL except for media pressure and hopes of goodwill.

But, as comrades in the Peruvian movement explained,

“Negotiations are reached by pressuring with persistence, and sharpening the struggle. Not like some say now, ‘stop struggling and let’s talk.’ […] In every struggle the time comes to dialogue, but at the negotiating table you can only win what you have already won at the battlefield; that is a fundamental military and political criteria.”[13]

As communists, we understand that the question of political power is the fundamental one: at any given time, the balance of forces in the struggle around the DC reflects the shifting levels of power which each side was able to bring to bear in order to influence the course of events. In a one-sided negotiation, when the SDC campaign was isolated from the masses and had no leverage, all negotiations took the form of begging for scraps from an organization whose interests opposed it.

So, as the aboveground SDC campaign increasingly demonstrated that it would be unable to meaningfully influence the eviction proceedings, the Direct Action working group began to implement its escalation plans. Ultimately, this entailed the transition from the ‘Save the DC’ campaign to the declaration of a ‘People’s Democracy Center’ (the PDC).

PREPARING FOR THE OCCUPATION

The development of the struggle to its highest stage, the transformation of the SDC campaign into the occupation of the PDC, occurred in one hurried week. And while the Direct Action working group was able to facilitate that transformation, they inherited errors from the SDC campaign and introduced new ones due to the rushed process of occupation planning and a failure to consolidate around a meaningful analysis of the situation. This resulted in the occupation of the PDC on June 30 becoming the escalatory high point of the sequence, rather than the start of its rising action.

This process began on June 23, when the Direct Action working group held a first and final rally to protest the closure of the space. After delivering speeches from the DC’s roof to a crowd assembled on the street outside, rally organizers invited attendees into the building for an unsanctioned meeting, where an occupation of the building was proposed. This was framed as a tactic of last resort against a landlord who refused to listen to the demands of the community, and as an alternative to the moribund strategy of the rest of the SDC project, which by then had effectively accepted the inevitability of the closure.

Through this mass meeting, the Direct Action working group was able to win over a substantial amount of support from unaffiliated attendees, who were recruited to begin the process of organizing and planning the occupation of the DC, in both logistical “support” roles and “high-commitment” roles inside the occupied building. This resulted in the formation of a number of new working groups, following the structural pattern set by the SDC campaign. Adherence to this model had the effect of limiting lines of communication and preventing the formation of an effective decision-making apparatus, key errors which led to the severe communications breakdowns and siloing of work which would characterize the end of the PDC some days later.

We wish to underscore here that the Direct Action working group’s strategy of treating occupation as a tactic of last resort was a significant political and practical error. As we established above, laboring for months under the illusion that negotiations with FCL could’ve forestalled the eviction did nothing to qualitatively advance the campaign, and was in fact disorganizing and demobilizing; an orientation emphasizing the need to seize control of the space directly therefore should have been pressed (and prepared for) from the beginning. Failure to do so left the left fraction in a position of needing to scramble to construct the necessary infrastructure when the moment for action had already arrived.

Consequently, instead of approaching the task of occupation with a plan already in place, the week after the rally was spent developing one. In addition to resulting in disorientation and a body of occupiers underprepared for the actual work required of them, this prevented the construction of a robust communications infrastructure capable of winning outside supporters to the cause of the struggle. Even if such an apparatus had been built, because the activists had prioritized practical questions over developing even basic unity around the political questions at hand—namely, resistance to gentrification and anti-Zionism—there was no path to a public narrative more substantive than condemning the loss of a community center. This lack of structure was so severe that when the individual who had been responsible for external communications effectively vacated their role altogether the night of the occupation, their departure was almost completely unknown to the occupiers inside the building. They had to be rapidly replaced after a mass demonstration (which had been planned to coincide with the announcement of the occupation) essentially failed to materialize because no public communication had taken place.

In the absence of a formal decision-making body, the “high commitment” group,” (the title given to the group taking part in the initial occupation and/or longer-term overnight presence) became the de facto leadership of the occupation, laying the groundwork for divisions between the “inside” and “outside” elements which became prevalent later. This was ostensibly intended to limit legal culpability for those taking ‘lower risk’ roles, but posed significant political problems because of isolated, undemocratic leadership and exposed the “high commitment” group to unnecessary personal risk by separating them from the masses. It also led to communications breakdowns as early as the July 1 rally discussed below.

The period immediately preceding the occupation involved a series of meetings. The composition of these meetings varied, but throughout the process, elements close to the old SDC campaign advanced a line pushing for the occupiers to link their demands (and outlook) to those of the old campaign. This was opposed by a left line coalescing in favor of more explicit politicization of the struggle and criticism of the DC’s failure to expel Zionist groups, but the right-opportunist line ultimately won out. This had the effect of further muddying the relationship between the occupation organizers and outside social movements, exemplified by the criticism levied during the days following the occupation’s collapse that it was unclear whether the occupation was a continuation of, or break from, the Zionist DC which had alienated the broader anti-Zionist movement.

Advocates of the right-opportunist line also pushed for consensus-based decision-making and a horizontal structure resistant to the development of a political leadership or criteria for political unity, further disorganizing the forces of the occupation. Beyond rotating “tactical” leadership (whose scope of authority was vague and undefined), no form of internal structure beyond group chats was ever established. But the absence of formal leadership didn’t mean that no one was “in charge,” just that who was making decisions was never clarified. Consequently, decision-makers (namely, a clique within the “high commitment” group) were entirely unaccountable to anyone but themselves, and there were no official channels for passing information or asking questions. Because there was no concrete leadership, decisions made during the community meetings preceding the occupation were never carried through, leading to the constant revisiting of problems without making substantive progress. Instead, the only decisions that persisted were made undemocratically and in isolation during meetings of the “high commitment” group.

Early in the morning of July 1, the “high commitment” group retook the DC, as planned and without incident or alerting the authorities. Doors were barricaded at the direction of tactical leadership, while others assembled sleeping areas. Though seeds of its collapse had been thoroughly sown, when the sun rose that morning it shined not on the old DC but on the People’s Democracy Center.

THE PEOPLE’S DEMOCRACY CENTER

The People's Democracy Center made its public debut with the initiation of a rally outside the DC at 8:00AM on July 1. Here, the problems created by the rushed preparation for the occupation and lack of clear organizational structure became apparent. The rally itself was announced publicly via an unaffiliated Instagram account a few minutes after it had already begun, the emcee canceled on short notice, and there were no speakers planned. The PDC's “safety team” (variously called a security working group, a safety team, a safety working group, etc.) had not been organized into a group to assist with coordination at the rally, which forced the scout team into taking up the task of organizing logistics for the demonstration. With no programming put together and short notice that the rally was happening at all, only a few people stood outside the Democracy Center at 8:00AM, primarily individuals who were involved with the PDC effort. Despite this, reports of a gathering outside of the building made their way to the Cambridge Police Department, who arrived on the scene shortly afterwards. In such a small crowd the radio-carrying scouts stood out like a sore thumb, causing them to be approached by the police upon arrival, and leading to the discontinuation of radio use by scouts for the remainder of the occupation. Finally, due to the continued lack of coordination, two members of the “high commitment” group inside the building went onto the roof of the Democracy Center in order to lead the rally from there. Confused by the display in front of them, and apparently having received no call to intervene from the Foundation for Civic Leadership, the Cambridge Police decided that the rally was merely a social gathering with no noticeable illegal activity, and eventually left.

The failure to coordinate the initial rally outside the People's Democracy Center was the direct result of the flimsy organizational structure adopted by the occupation because of the influence of the right-opportunist line. As established above, while the activists of the PDC had been organized into a number of different working groups to oversee the completion of certain practical tasks, there was no formal leadership structure tying these various groups together. Taking influence from the structure of the SDC campaign, the PDC’s closest analogue to a leadership body was a shared coordinating group chat where each working group was represented by one or two points of contact. The function of this chat was hence relegated to point people from this or that working group passing along information to the other working groups, but, because there was no official leadership structure within this coordinating channel, these messages often did not elicit concrete actions in response. Unless a point of information was clearly actionable, obviously pertained to a specific working group, and was addressed directly to the relevant working group—a set of criteria frequently not met—such communiques were likely destined to remain one-sided, seen and heard by the other point people but with nobody taking ownership of responding in either words or actions.

The inability of the People’s Democracy Center to coordinate its opening rally was a direct consequence of this horizontal structure, as without a unified organizational center empowered to communicate, coordinate, and delegate across its disparate bodies, communications between subgroups inevitably broke down, tasks inevitably fell through the cracks, and people inevitably deferred to informal leaders who allegedly did not exist. We say “allegedly” here because, as we shall see, these structures rarely if ever actually exist without leaders; leadership is not avoided, but rather kept informal and implicit, emerging not from democratic processes accountable to the people they directed, but rather from existing social networks and clout.

At approximately 10:00AM the rally was concluded, and the attendees were invited inside the People's Democracy Center for a community meeting. In this meeting the predisposition towards a “vague consensus” model as a decision making process caused further problems. This model was another aspect of the PDC derived from its origins in the Save the Democracy Center campaign, where group decisions were largely only arrived at once unanimous support had been attained. Moreover, the permanence and conclusiveness of these decisions, even once arrived at, was often unclear, leaving topics open to be revisited in the future. Such a decision making process can result in paralysis, as establishing unanimity on any given topic is quite difficult, and such progress can be wiped away the instant the group chooses to again hem and haw over something which was already decided. And this is what happened in the very first community meeting of the PDC; the meeting was almost entirely focused on rehashing decisions already arrived at prior to the launching of the occupation, keeping the PDC stuck reevaluating what it had already resolved, rather than pivoting to what needed to be done. This left two essential topics unaddressed: physically securing the space itself, and politicizing the struggle. This organizational paralysis thus enabled by default the continuation of the PDC’s inherited depoliticization.

For the People’s Democracy Center, the question of physically securing the building was inseparably bound up with the question of politicization, and while some attempts were made to develop appropriate security measures to protect the occupation, politicization itself was utterly neglected. Though activists in the PDC labored to secure some of the space by use of barricade, and sought to practice information security by relegating phones either to a bucket at the entrance to the building or to a designated ‘phone room,’—itself a deeply unserious practice which represented more of a security flaw—in actuality, politicization of the struggle was the surest method for defending the occupation.

This is because an occupation, and moreover any center of struggle, is at its most secure when it surrounds itself, immerses itself in the masses. Literally, for the PDC, this meant having people physically present not just inside the building, but outside, surrounding it. On the other hand, being isolated from the masses, not having sufficient people around the building, represents a fatal weakness, a vulnerability which would surely be taken advantage of by the FCL and the police. But to mobilize the masses in defense of the People’s Democracy Center, the masses would first need to be told why the struggle around the Democracy Center was important in the first place. This is the objective of politicization; to place the occupation of the Democracy Center in the context of the political struggles against capitalism, to give it meaning via its connections to anti-Zionist and anti-gentrification struggles, to rally the masses around an outbreak of political struggle which seeks to land concrete blows upon our class enemies. Yet despite the central importance of politicization to the success of the People’s Democracy Center, it remained unaddressed within the occupation’s first community meeting.

In fact, not only had there still not been any public articulation of the occupation's political outlook or even its demands, but it also became apparent over the course of this meeting that the mechanisms to make such public articulations were not in place as the Communications/Community group remained unable to complete its tasks due to lack of internal structure or delegation.

The Community/Communications group, like the other working groups, suffered from many of the same problems inherent to the horizontal, group chat organization, but exacerbated by a number of additional factors. In large part it conducted its work remotely without ever conducting an in-person meeting, meaning the working group existed entirely as a group chat. Furthermore, as can be noted by the name “Community/Communications,” the working group seemed to be something between an actual working group tasked with communicating with other groups and with the masses, a working group for planning events and coordinating said events with the people on the inside, and a large holding chat for “community members” interested in the People’s Democracy Center. This meant that not only was the working group a group chat trying to substitute for an organized body, but also that it was a bloated group chat filled with near-to-completely inactive spectators and overlapping activists who were members of other working groups. This left it uniquely unable to accomplish its objectives.

To address the immediate practical failings of the working group, a few attendees of the initial mass meeting were recruited to take up some of the tasks that had been falling through the cracks, primarily setting up and managing an Instagram account and an email address for disseminating information from the occupation. Following the entry of these new members, the existing point person for the Community/Communications group officially withdrew from the organizing effort, citing a lack of capacity to continue (after having de-facto vacated the role several days before). By the end of the meeting (around 12:00PM), a series of events for the day had finally been announced on the official People's Democracy Center Instagram account.

Four events were announced for the evening of July 1, each slated to last for an hour, spanning the time from 3:00PM to 7:00PM. These events were to be, in order, two musical performances, a reading group, and a teach-in by a few local street medics. Yet in the lead-up to and during the two musical performances, employees from the Foundation for Civic Leadership began approaching the occupants of the People's Democracy Center in an attempt to initiate negotiations for the end of the occupation. Soon, a rumor began to spread that the FCL representatives had been overheard speaking with their employer over the phone about setting a 7:00PM deadline for the occupation to vacate the building before they would be forcibly removed. This led to a second meeting being held after the second musical performance to discuss how to proceed given the possibility of an ultimatum from the FCL, and after an hour of deliberations, it was decided to proceed with the scheduled programming and remain in the building.

It was further decided to call for an emergency rally to defend the occupation that night, though, similar to the gathering which took place in the morning, few efforts were actually made to coordinate such a rally. As a result, there was no follow-through on putting together programming for the emergency rally, and those who did show up either entered the building for the previously announced events, watched as negotiations with the FCL employees continued, joined the occupation, or took on external roles which still needed more people, principally scouting roles.

During the medic teach-in, one of the coordinators from the scout team who had been spending a significant amount of time on the ground entered the building and approached the clique of activists perceived as the PDC’s de-facto leadership. This particular clique had been the strongest force advocating for the horizontal, consensus-oriented line, and as such, actively eschewed leadership, and ostensibly resented that they were being treated like they were in charge. Nonetheless, attendees and members of the occupation were increasingly coming to them looking for guidance because of their existing clout.

The scout team member raised several issues, principally a lack of available volunteers, and failures in communication and coordination both internal to the scout team and between the scouts and the occupation itself, highlighting in particular that it was proving exceedingly demanding for a small number of people to coordinate 24/7 surveillance of the Democracy Center with little guidance from the team occupying the space. This scout further highlighted the glaring security concern that there were too few people surrounding the building on the outside, leaving the occupation isolated from its supporters and more vulnerable to a police raid. Indeed, as the night progressed, more and more people had left the building and no one but the scouts remained outside, leaving only a core of activists within the Democracy Center itself. While a few new activists were able to be recruited to the scout team, these concerns were by-and-large left unaddressed, and little support was offered to improve coordination other than suggesting that the scout team “figure it out themselves,” despite struggle within the “high commitment” group over developing stronger support structures.

Despite these security concerns, and despite the failure to coordinate an emergency rally which surrounded the building with a protective crowd of people, again the enemies of the People's Democracy Center simply did not take action; the rumored 7:00PM deadline to vacate, real or not, never materialized, and the occupation was left uncontested for its first day of existence.

Early in the morning on July 2, an individual in the informal leadership clique began planning to hold a rave in the People's Democracy Center, and subsequently put up a post announcing the rave on the PDC's official Instagram, bypassing both the Community/Communications group and agreement from the occupation at large in doing so. Shortly thereafter, the Community/Communications group began receiving sharp criticism for the announcement, including that the event posed security risks, that the framing of the event made it possible to construe the rave as being pro-Independence Day, and that the event would be a social gathering in an actively occupied building whose occupiers urgently needed to politically agitate but continued to fail to do so. Because of these concerns, the Community/Communications group subsequently took down the Instagram post. The specific criticisms raised regarding the rave were passed along to the individual who wanted to host it, to which they gave no response.

A slate of other events was announced for the day, including a musical performance, a teach-in, two screenings, an art and banner build, and another community meeting. But again severe shortcomings in coordination began to flare up. While the day got off to a well enough start with the musical performance—sparsely attended as it was—the teach-in wound up canceling outright, and there was nobody onsite to actually coordinate setup for the latter screening, causing it to be pushed back in the schedule and eventually canceled.

PRELUDE TO COLLAPSE

On the evening of July 2 another mass meeting was held inside the PDC. This meeting continued the trend set by the prior meetings held in the occupation: an eclectic set of topics which were not derived from an analysis of the conditions the occupation actually faced, nor the key questions which followed from those conditions. Notably, the ongoing failure to provide the occupation with political content was relegated to a brief aside at the meeting’s close, because a consensus-based discussion regarding the state of the negotiations took up the bulk of the allotted time (only to re-assert conclusions arrived at in a previous meeting). Furthermore, the scout team was essentially excluded from discussion during the meeting because they were needed outside.

This prompted one attendee, an activist involved in the anti-Zionist movement, to raise several criticisms about how things were being run, including the failure to address imminent threats to the security of the occupation which had also been raised by others both within the building and by those who were supporting the occupation outside. These included poor barricading of one of the doors, failure to disseminate a plan on what to do in the event of police action, and the lack of any mass presence outside the building to dissuade potential police action.

In response to these criticisms an agreement was reached to call a rally outside the occupation that night, which could facilitate more direct outreach to the masses on the part of the occupiers and ensure that there was continuous mass presence outside of the building. Delegation of tasks for the rally followed: two members of the “high commitment” group’s leading clique instructed the scouts that they should form a line around the building and act as security, a task far out of scope for the risk level promised to those in the scout role and which had not been discussed during the meeting. In practice, the role of the scouts was in fact among the highest risk positions in the occupation, due to their visibility and isolation outside of the building.

As this process continued, more people gathered outside and talked with the scouts, unaware that they had been asked to run security. Some of the scouts (and others present) brought up concerns about the naivety of the “exit plan” (such as it existed) and sudden attempt to transform their role and asked to give input. The two “tactical leads” agreed to bring people inside to continue discussions, but became increasingly hostile towards them, after which communications deteriorated. Several outside supporters, primarily those recruited from the anti-Zionist movement, later expressed that they had left this encounter reporting that their feedback was shut down, that they were being disrespected, and that members of the “high commitment” group had engaged in a pattern of white chauvinism by dismissing constructive criticism and advice from organizers from oppressed nations.

Then, abruptly and without mass input, one of the “tactical leads” made a unilateral decision to cancel the rally and began directing people not to complete necessary preparatory work, while also asserting that the occupiers should not hold another meeting to discuss the concerns raised by the scouts and other “outside” supporters. Plans began shifting without clear direction, and tensions began to emerge inside the building, exacerbated by the confrontational tone increasingly being taken by the de facto leadership clique.

Meanwhile, social media posts announcing a rave were once again published, with no broad support, overriding the previous decision to cancel the event. No communication about this decision was shared with the Communications/Community working group, which learned about it only when they discovered the new post was live.

Throughout the night and the next day, the scouts, and other outside supporters, continued to levy increasingly direct criticism towards the occupiers and “high commitment” group, emphasizing a number of points:

1- Lack of politicization (beyond the public documents shared by supporting organizations on social media, which had themselves become points of conflict between the left and right-opportunist lines within the PDC);

2- Failure to provide substantive direction or structure to “outside” supporters in logistical roles, such as the scouts, as a result of poor organization overall.

3- Insufficient assessment of the risks of repression faced by the occupiers and their supporters;

4- Continued emphasis on the proposed rave, and the apparent lack of a security plan to ensure the safety of attendees should the rave actually occur

5- General lack of seriousness around the security of the occupation

6- White chauvinism on the part of the “high commitment” group

As discussion of these criticisms continued among those inside the building, the rave announcement was removed (again), and plans for a rally the following night were made in order to respond to the concerns raised earlier in the day. These plans were unable to reach fruition, as the building was evacuated by the afternoon of July 3.

EVACUATION AND AFTERMATH

Early in the morning on July 3, FCL announced their intention to bring in the police to expel the occupiers. Heeding an emergency call for a rally, supporters began gathering outside of the PDC. By this time, the breakdown between the “inside” forces and the “outside” supporters (both in scouting and logistics roles as well as sympathizers unaffiliated with the organized forces) had become irreconcilable, as entrenched opposition to organizational structure led to informal dictatorship by a clique within the “high commitment” group. This loosely anarchist clique resisted establishing both tactical unity with the scouts and political unity with the anti-Zionist movement, and enforced a tyranny of structurelessness which ensured that there could be no productive venue for criticism & self criticism. This lack of tactical unity and the isolation of "inside" forces directly contributed to the unrealistic labor expectations put upon the scouts. As was discussed above, this disunity also caused deep interpersonal tension, some of which was informed by white chauvinism on the part of the “inside” forces.

While police began to gather outside the PDC, “inside” forces made last minute calls to an anti-Zionist organization who had organized an unrelated demonstration elsewhere in Cambridge, requesting that they march their demonstration to the PDC to help head off the impending eviction. This reliance on anti-Zionist protesters and the progressive masses of the city for safety contrasted explicitly with the de-centering of Palestine in the struggle over the PDC, a de-centering which directly resulted from liberal depoliticization. Through sheer inertia, as the occupation's threadbare structure could not mobilize to correct course, previous hand-wringing from liberal forces during the SDC campaign about being perceived as opportunist directly lead to real, practiced opportunism. Despite this, the anti-Zionist organization did agree to move their rally, marching in solidarity to the PDC.